In Which Direction and by How Much?

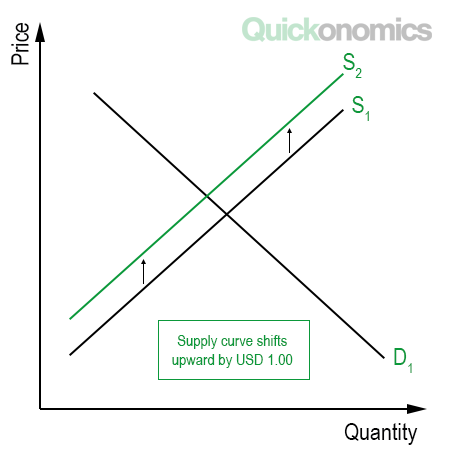

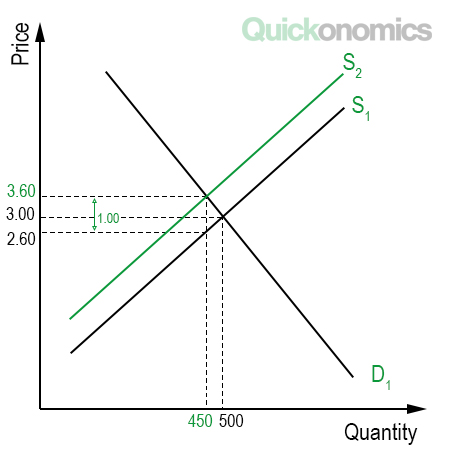

Now that we know which curve shifts, we need to find out in which direction and by how much. Luckily, this is quite simple. Taxes can be seen as additional costs, so they reduce the market. Therefore, as a rule of thumb, they shift curves to the left. More specifically, a tax on sellers shifts the supply curve to the left (i.e., upwards) whereas a tax on buyers shifts the demand curve to the left (i.e., downwards). The magnitude of the shift is always equal to the exact size of the tax. However, it is critical to note that this does not mean the market price will shift by the same amount. You can see this in the illustration below.

To illustrate this, let’s revisit our example. The initial market price of a burger is USD 3.00. With the tax of USD 1.00, the effective market price (i.e., the price sellers receive after paying the tax) is USD 2.00. As a consequence, sellers will make less profit and therefore, only supply the number of burgers they would provide if the market price was USD 2.00. Thus, the supply curve shifts to the left by the exact size of the tax.

What is the New Equilibrium?

With the information we have collected so far, we can now find the new equilibrium and calculate the tax incidence. As mentioned above, taxes reduce markets, so the new quantity supplied will be lower than without the tax. At the same time, if the tax is levied on sellers, market price increases, whereas it decreases if the tax is levied on buyers. It is important to note that the tax incidence does not depend on who the tax is levied on. The distribution of the burden will be the same, whether the tax is imposed on buyers or sellers.

In our example, the new equilibrium price is USD 3.60 per burger. That means, the sellers pass on a share of their burden to the buyers, who now have to pay USD 0.60 more per burger than before the tax. Meanwhile, the sellers effectively only receive USD 0.40 less for each burger they sell. Hence, buyers carry 60% of the tax burden, and sellers carry 40%. That may seem odd, given that the tax was imposed on the sellers and not the buyers, right? Well, yes. But again, this does not matter when it comes to tax incidence.

Tax incidence depends on the elasticity of demand and supply. If the demand curve is more inelastic than the supply curve, buyers have to carry a larger share of the tax. Analogously, sellers have to carry a higher tax burden if supply is less elastic than demand. In other words, the side that has a relatively more inelastic curve (i.e., reacts less to price changes) has to carry a larger share of the tax burden, regardless of who the tax is initially levied on.

In a Nutshell

Taxes can be levied on buyers or sellers. However, who actually pays a tax does not depend on who it is levied on. In economic theory, tax incidence – which refers to the distribution of a tax burden between buyers and sellers – only depends on the elasticity of supply and demand. To calculate tax incidence, we first have to find out whether the tax shifts the supply or the demand curve. Next, we can determine in which direction and by how much the curve shifts, which finally allows us to find the new equilibrium and measure the tax incidence. In general, the side that has a relatively more inelastic curve has to carry a larger share of the tax burden, regardless of who the tax is initially levied on.