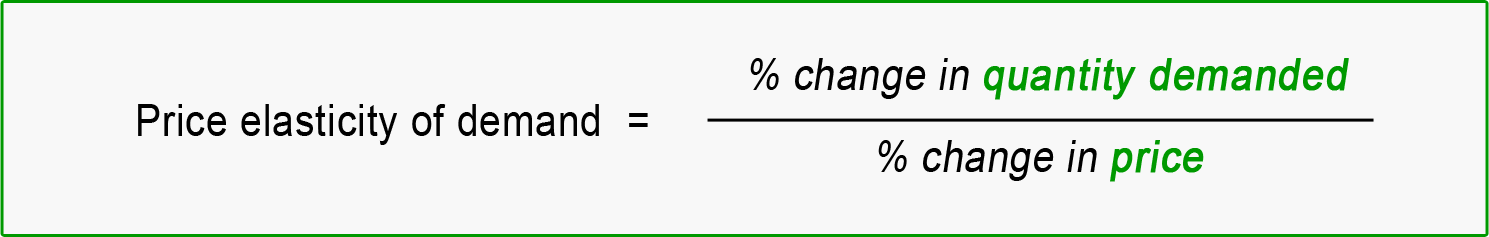

Updated Jun 26, 2020 The PED is determined by a multitude of economic, social, and psychological factors that each influence consumer preferences and choices in a unique way. The most important ones are the necessity of the product, the availability of close substitutes, the proportion of income devoted to the product, and the relevant time horizon. If a good is considered a necessity (e.g., water, bread, toilet paper, etc.), a large change in the price of the good won’t affect its demand significantly. In that case, we speak of inelastic demand. The reason for this is that people always have to satisfy their basic needs, so they do not respond much to price changes for basic goods. If a product is considered a luxury good, however, demand will be much more elastic because people do not need those products to survive. Close substitutes allow consumers to switch between different goods that satisfy the same (or similar) needs. Thus if a good has one or more close substitutes, demand will be rather elastic. In that case, people can buy the substitute to satisfy the same needs if the price of a product increases. On the other hand, if there are no close substitutes available, consumers cannot just switch between similar products so they won’t respond strongly to a price change. Products that are expensive (i.e., take up a high proportion of the available income) tend to have more elastic demand. In absolute terms, a 1 percent increase in the price of an expensive good is more significant than a 1 percent change in the price of a cheap good. As a result, consumers generally respond more strongly to price changes if they have to devote a larger proportion of their income to a certain product. In most cases, demand is more elastic in the long run as it is in the short run. There are many occasions where consumers face high switching costs in the short-run (because of binding contracts, opportunity costs, etc.). Those costs are usually lower in the long run because contracts can be allowed to expire, and there is more time to prepare and to evaluate all available options. There are different types of elasticity. In particular, a demand curve can be elastic, unit elastic, or inelastic. Since elasticity is always measured at a certain point, a single curve can have segments of all three types simultaneously. To see how this is possible, we will have to crunch the numbers and look at how elasticity is computed. The PED is defined as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in the price of a good. This can be illustrated using the following formula. To give an example, let’s assume that an increase of 2% in the price of ice cream causes consumers to buy 6% less of it. According to our formula, the elasticity, in this case, can be computed as 6% / 2% = 3. So the price elasticity of demand equals 3. Please note that in some cases, we need a new formula (i.e., the midpoint formula) to calculate the price elasticity of demand. More specifically, the midpoint formula is required when we try to calculate elasticities between two points on a demand curve. In addition to that, we also need some classification to work with the number we calculated above. Right now, it does not say much. This is where the different types of elasticity mentioned above come into play. With their help, we can classify the curve and thus interpret the result. The cross-price elasticity of demand is used to measure by how much the quantity demanded of a good changes as the price of another good increases. Thus, it is defined as the percentage change in quantity demanded of good 1 divided by the percentage change in the price of good 2. This results in the following formula. If the cross-price elasticity is a negative number, the two goods are said to be complements. In this case, an increase in the price of good 1 reduces the demand for good 2. On the other hand, if the elasticity is positive, the goods are said to be substitutes, since an increase in the price of good 1 results in an increase in the quantity demanded of good 2. The income elasticity of demand is used to measure to what extent the quantity demanded of a good changes as consumer income changes. It can be computed as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in consumer income. Again, this can be illustrated using a simple formula. If the income elasticity of a good is a positive number, it is considered a normal good, because a higher income increases the quantity demanded. By contrast, if the good has a negative income elasticity, it is regarded as an inferior good. In the case of those goods, a higher income will result in a lower quantity demanded.Determinants

1) Necessity of the Product

2) Availability of Close Substitutes

3) Proportion of Income Devoted to Product

4) Relevant Time Horizon

Types of Elasticity

Additional Demand Elasticities

1) Cross-Price elasticity of demand

2) Income Elasticity of Demand

Summary

Microeconomics