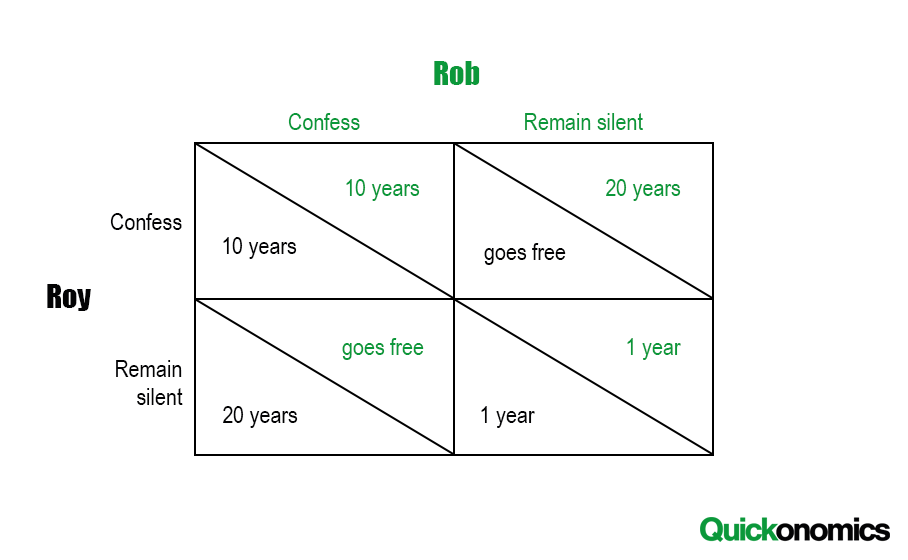

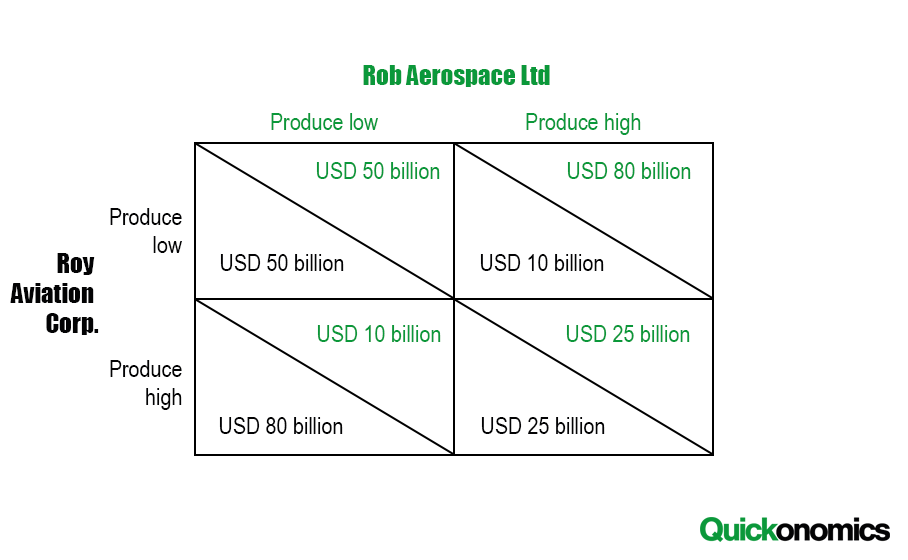

Updated Dec 30, 2022 The prisoner’s dilemma is arguably the most famous example of game theory. It describes a situation (i.e. game) between two prisoners, who act in their own self-interest, which results in an inefficient outcome for both of them. In essence, the prisoner’s dilemma illustrates why it can be difficult to maintain cooperation even when it is mutually beneficial. So let’s look at it in more detail. Game on! As mentioned before the prisoner’s dilemma concerns two prisoners (i.e. players). Let’s call them Rob and Roy. They have been arrested after robbing a bank together. Unfortunately, the police only have enough evidence to charge them with illegal possession of firearms. Unless at least one of the two prisoners confesses, it will not be possible to convict them for the robbery. To increase the chances of obtaining a confession, the police question both criminals separately. First, they talk to Rob. The interrogator tells him that they have enough evidence to lock him up for at least 2 years if he remains silent. However, the police offer him a deal. If Rob confesses to the robbery, he will be given immunity and can go free, while Roy will face 20 years of prison. Of course, the interrogator also lets Rob know that Roy will be offered the same deal. Similarly, if Rob remains silent but Roy confesses, Rob faces 20 years in prison, while Roy goes free. If both of them confess, they get to share the sentence and both spend 10 years behind bars. What is Rob’s best choice in this situation? He has two strategies: confessing, or remaining silent. However, the amount of time he has to spend behind bars also depends on which of those two strategies Roy chooses. Thus we say, Rob and Roy are in a strategic relationship. When taking his decision, Rob has to anticipate what Roy will do, because this will affect him as well. If his partner in crime remains silent, Rob can go free if he confesses. However, if Roy decides to confess, Rob is better off confessing as well. This way, they get to share the sentence and Rob does not have to spend 20 years behind bars alone. From an individual perspective, Rob is always better off confessing, regardless of what Roy does. To illustrate this, you can find all possible outcomes in the matrix below. If we assume that both Rob and Roy act in their own self-interest (which seems obvious, given they are criminals) they are both going to confess. From an individual perspective, this is their best option. We call this a dominant strategy. No matter what the other player does, a dominant strategy is always the best option. So in this case, they both end up spending 10 years in prison. You are probably wondering how this can be a dominant strategy (i.e. best option) if they could both get away with just 2 years if both of them remained silent. That’s is a good question. At this point it is important to note that the dominant strategy is defined from an individual perspective. From an overall perspective, they would indeed be better off cooperating. That’s why it’s a dilemma. Even if they had made an agreement before they were arrested, once they are questioned, both of them have an incentive to cheat and go free. As soon as they are separated, self-interest takes over. Simply put, in this case, cooperation is irrational from an individual perspective, which results in an inefficient outcome. Of course the prisoner’s dilemma does not only occur in prisons. We find similar situations in various economic settings. Think about oligopolies, for example. Let’s say there are two Firms, Rob Aerospace Ltd. and Roy Aviation Corp. For the sake of the example, we will assume they are the only two players in the airplane market. If they don’t cooperate and work at capacity, they share the market. Alternatively, they can agree to keep production low. If they do that, they still share the market, but they can drive prices up (see also Supply and Demand). As a result, both firms can increase profits. However, if they agree to keep production low to increase prices, both also have an incentive to defect (i.e. break the agreement) and sell more airplanes at the higher price. If they do this, they increase their profits at the expense of the other player. Again, let’s look at the matrix to see all possible outcomes. When we look at the matrix, it becomes apparent, that the dominant strategy for Rob Aerospace Ltd. and Roy Aviation Corp. is to defect and produce more airplanes, regardless of what the other firm does. As a result, the market price falls and so do profits. This example beautifully illustrates why oligopolies often have a hard time maintaining monopoly profits. The logic is the same as before; from an overall perspective, it is rational to produce a lower output at a higher price for both of them, but from an individual perspective, they both have an incentive to defect and increase their own profits even more. To give a few more examples, we can also look at arms races or common resources. In an arms race, two countries spend huge amounts of money on arms and weapons to ensure their military power. From a global perspective however, they would be better off spending that money somewhere else (e.g. education, healthcare). Similarly, people tend to overuse common resources, such as drinking water from a well. Ironically, this happens mostly because they are afraid other people might use too much water, which could drain the well and leave them without water. Now that we have seen why it can be difficult to maintain cooperation, let’s look at how we can increase the chance of cooperation. We can add an interesting twist to the prisoner’s dilemma if we assume the game is played several times in succession (i.e. repeatedly). In this case, the players are actually more likely to cooperate. Now they are engaged in what we call a continuing strategic relationship. This kind of relationship is different from the strategic relationship we find in the regular prisoner’s dilemma (see above) mainly because the actions taken by the players in one round affect their relationship in subsequent rounds. If a player cooperates, it can be seen as a signal that he or she is likely to cooperate in future rounds as well. In other words, the players can build up a reputation. Of course, both parties can still defect and break their agreements. However, if they do so, they will be punished in future rounds. The other player won’t cooperate anymore once he or she has been cheated. This harms both of them in future rounds. In the long run, they are both better off cooperating. Of course they can anticipate this when deciding on a strategy, which will in most cases encourage cooperation. The prisoner’s dilemma is an example of game theory that illustrates why it can be difficult to maintain cooperation even if it is mutually beneficial. It describes a situation (i.e. game) between two prisoners (i.e. players) who act in their own self-interest, which results in an inefficient outcome for both of them. However, if the game is played repeatedly, cooperation is more likely to occur, because defection can be punished in future rounds.The Game

The Dominant Strategy

Economic Examples

Repetition and Reputation

In a Nutshell

Microeconomics